Tekke Bird Asmalyks

Who wove the so-called Tekke Bird Asmalyks?  Seems like a simple enough question yet today there still isn’t a consensus answer. In fact these venerable objects are only called asmalyks because of their five sided appearance and lack of a back. After reading Robert Pinner’s seminal article in Turkoman Studies One, concerning these weavings, it appears they were woven in pairs. It doesn’t appear to me that the classical Tekke Bird Asmalyks were produced after the mid 19th century. Only Tekke examples with non traditional designs are known to have been woven after the mid 19th century. There are far too few Tekke Bird Asmalyks for them to have been wedding accoutrements, considering the number of Yomud asmalyks extant. Considering the number of Tekke Bird Asmalyks in museums and private collections, I theorize that they were turned over and recreated anew about every thirty or so years. This would imply that only three or four pairs were produced every century. The end of the Tekke Bird Asmalyk genre of weaving probably coincided with the suspension of the Great Hunt as a Tekke social institution. If any Great Hunts were conducted by the Tekke while at the Merv Oasis, from about 1847 to 1882, no information has survived chronicling the fact.

Seems like a simple enough question yet today there still isn’t a consensus answer. In fact these venerable objects are only called asmalyks because of their five sided appearance and lack of a back. After reading Robert Pinner’s seminal article in Turkoman Studies One, concerning these weavings, it appears they were woven in pairs. It doesn’t appear to me that the classical Tekke Bird Asmalyks were produced after the mid 19th century. Only Tekke examples with non traditional designs are known to have been woven after the mid 19th century. There are far too few Tekke Bird Asmalyks for them to have been wedding accoutrements, considering the number of Yomud asmalyks extant. Considering the number of Tekke Bird Asmalyks in museums and private collections, I theorize that they were turned over and recreated anew about every thirty or so years. This would imply that only three or four pairs were produced every century. The end of the Tekke Bird Asmalyk genre of weaving probably coincided with the suspension of the Great Hunt as a Tekke social institution. If any Great Hunts were conducted by the Tekke while at the Merv Oasis, from about 1847 to 1882, no information has survived chronicling the fact.

Drawing heavily on a lifetime of collecting Tekke weavings along with studying the writings of Robert Pinner, Edmond O’Donovan, Jon Thompson, and E.H. Parker I have framed my interpretations of their designs.

The horse, the raptor, the dog, and the bow and arrow were the constant companions of any self respecting Turkoman man. Taken together as a unit; the raptor, horse, dog, and bowman constituted the most powerful weapons configuration in the world. It wasn’t until the deployment of suitable firearms in the 19th century that the Tekke were finally defeated in 1882 at the Merv Oasis. I hope that carbon 14 testing can be done on every Tekke Bird Asmalyk extant sometime in the future and those results get published.

The most recent and supremely successful horse mounted archer King was Genghis Khan. The 13th century ways of the last Great Khan’s Golden Horde became the stuff of stories and legends among the horse mounted tribes surely including the Tekke, considering their many centuries on the steppes of Asia.

Extrapolating from the above premise the rite of passage for any young Tekke boy would have occurred during the Great Hunt; just like it was done in the time of the last Great Khan. Heather Daveno wrote; “Training (of youth) for the Mongolian army took the form of the hulega, or Great Hunt, a slow, circular advance made at a steady pace which they called the wolf lope. It was conducted like a campaign and was designed to teach discipline, strategy and unity under command. From the Yassa or law of the Great Khan we read in law 27, “He ordered that soldiers be punished for negligence; and hunters who let an animal escape during a community hunt he ordered to be beaten with sticks and in some cases to be put to death.” I theorize that the end of the Tekke Bird Asmalyk genre of weaving coincided with the suspension of the Great Hunt as a social institution. Unfortunately there are no written accounts, that I have been able to find, concerning a first hand account of the Tekke version of the classical Great Hunt festival.

I hypothesize that all Tekke Bird Asmalyks were decorations for the Tekke Khan’s mount at this once every two or three year event. I believe the item itself testifies to this fact through clear pictographic representations of such a Great Hunt. To properly imagine any authentic Turkmen experience one must include the aural sensations along with the visual. At the initiation of the Great Hunt, I imagine the Tekke Khan arriving on his ceremonial mount bedecked with weavings such as the aforementioned bird asmalyks. Certainly the boys’ heads were filled with the excitement of novel sights and sounds surrounding them.

After the Tekke Khan signaled the Great Hunt to begin many boys on horseback, with bows and arrows at the ready, were released into the game rich interior trying to kill game animals from horseback. Almost immediately the air would have filled with the twanging of bowstrings, the whistling of arrows, and the deep thud of arrow impacts. It was necessary to kill something in this way in order to be called a true Tekke man. I have discovered that it is very difficult to kill anything, in the game animal category, with a bow and arrow. Killing a game animal from horse back would be many times more difficult and the skill required extreme.

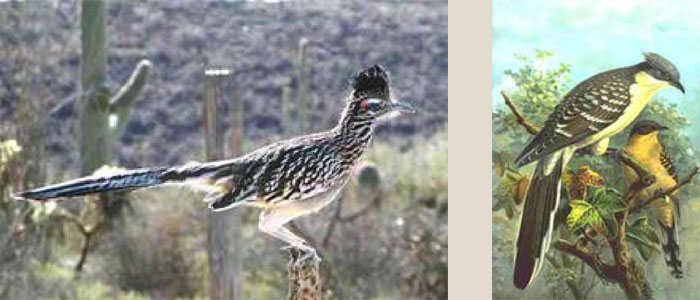

What I see when I look at Tekke Bird Asmalyks is a tangential or 45 degree array of ‘twanged’ bowstrings terminating at nodal arrow nocks, full bows represented with two drawstrings indicating they have just been shot, two headed generic animal forms, and a group of large well articulated sacred Tekke bird forms. The Tekke sacred bird probably represented a ground hunting fast running species with limited flight ability, like the ubiquitous Roadrunner species. The actual species of bird that is most likely represented in the Tekke Bird Asmalyks is the Great Spotted Cukckoo, Clamator glandarius. Fig. 3

The photograph above, fig.2 is of the North American version of the Central Asian species and the colored drawing; fig. 3 represents the native Turkmenistan Great Spotted Cuckoo. I included the American version because it shows the erect crest.

The biological facts about this ubiquitous species reads like a listing of ideal Tekke characteristics. Roadrunners are quick enough to catch and eat poisonous snakes. Roadrunners prefer walking but running they can attain speeds of up to 17 mph. The Roadrunner looks like a bird of prey when it is seen flying. The Roadrunner’s desert adaptations include reabsorbing water from their feces before excretion. The Roadrunner’s nasal gland eliminates excess salt, instead of using the urinary tract like most birds. This trait is shared with Galapagos Iguanas. Roadrunners are exemplary desert adapted inhabitants of the world’s great semi arid regions in ways much admired by the Tekke.

In my opinion this birds characteristics would have made it the perfect symbolic match for the classical era Tekke horse-mounted archer’s sacred bird. There can be little doubt that the classical era Tekke nomad would have been aware of the many biological adaptations this species exhibited in its’ daily life.

The striding legs of the large sacred bird forms in some Tekke Bird Asmalyks are represented with a form familiar to us from Tekke main carpet gulls. This form resembles an arrow piercing flesh , a lance stuck in the ground, or a set of menacing claws. Such associations of the bird’s legs with fast moving objects implies speed. I believe this association should be understood to mean that Tekke sacred birds were fast runners.

Since riding a horse came naturally to all Turkmen boys, they rode ponies as soon as they could walk, their main obstacle, during the great hunt, would have been using their bow and arrow to kill game animals. By correlating images from everyday Turkoman experience with the list of iconographic forms found in this Tekke Bird Asmalyk I have managed to explain or map most of its iconographic relationships to real world objects.

The archetypal pictographic device for the idea ‘to hunt’ was identified by Robert Pinner as dating to Shang dynasty China.

In the ancient Shang dynasty, a pictogram meaning ‘to hunt’ was developed that resembled two archetypal animal forms flanking an arrow’s projection thru space, via linear elongation, released from a bow form, surmounted by a simple bird design. See page 212, figure 443, in Turkoman Studies One. The archaic animal forms seen here may in fact be idealized reconstructions of dinosaur bones, as the veneration of huge bones was wide spread in Shang dynasty China as well as in ancient Rome and Greece.

The general elements that the Shang period pictogram embodies are carried forward, within the paradigm of known Tekke Bird Asmalyks, though stylistically amplified. My understanding of the Shang dynasty pictogram amounts to a visual expression meaning “anything can be killed with my arrow as long as the birds are my allies”, or perhaps, “my arrow flies like a bird to kill my prey”. I attribute such an amazing continuity of symbolic similarity to the simple fact that both pictograms deal with similar subject matter brought forth from the same deep wellspring of subconscious process.

I think pairs of Tekke Bird Asmalyks were created for Tekke Khans, through the generations, for the decoration of The Khan’s personal mount at the Great Hunt, where young warriors proving their prowess as hunter killers got elevated to adult status.

The classical Turkoman dowry weaving, whenever observed in situ, instantly identified the work of a specific set of hands. The symbolic relationships expressed in Turkmen weaving were also instantly recognized as including a specific weaver into a specific group of people, the clan, and as a member of a specific type of people, the larger tribe or horde. Finally the total impact of Turkmen dowry weavings served as a general appeal for love and acceptance and more specifically as an advertisement for marriage. I think it is clear that Turkmen dowry weavings constituted the physical expression of a human language utilizing pictographic representations of multilayered visual ideas for its syntax. Utilizing my linguistic paradigm I deconstruct the iconography of a representative Tekke Bird Asmalyk below.

In figure four, I see iconographic forms relating to the most salient elements of an archetypal great hunt. In the visual center of each major design complex strides the Tekke sacred bird. The surrounding image is that of a plucked bowstring. A plucked bowstring is similar in some ways to a twanged guitar string. After plucking a tightly strung bowstring, in the right light, two bowstrings momentarily appear as the spatial summation of the plucked string’s oscillatory maxima and minima. It was precisely special observations such as this that one should expect to see included within the classical Tekke pictographic gestalt indicating the collective hunt. On the back of the sacred bird in figure four is a bow form. The appearance of a double bowstring associated with this bow and arrow implies that an arrow has been shot.

The sacred bird form is physically touching an elaborate diamond design that symbolizes the game enriched territory that has been ‘roped off’ for the Great Hunt. The opposite side of this diamond form touches a complex set of arrow related motifs. As one fits an arrow’s nock onto a bowstring a small section of nock obscures the string and this small section of an arrow’s nock is illustrated by the dark blue triangular from seen at the most dependant extreme of this nodal design complex. The two fingers the archer uses to shoot his arrows are illustrated in deep blue forms to either side of the exposed nock tip. This is literally an up-close visualization of the act of releasing an arrow.

The relatively long hexagonal apricot form just superior to the blue nock tip containing an oblong purple center symbolizes the entire nock and string assemblage. At its superior end this form engages a fully pulled or drawn bowstring. The overall gestalt of this arrangement is one of extreme tension. The feather like appendages attached to this nock, plus fingers, plus bowstring design complex are meant to represent the sound of a twanged or released bowstring, like a leaf vibrating in the wind. In fact the lower set of leaves in fig. 4 clearly shows two interior dashed lines possibly indicating the oscillatory nature or the double appearance of a twanged bowstring. The upper set of leaves in fig. 4 may then indicate the return through time to a single bowstring appearance. In the authentic Tekke milieu at any Great Hunt a native Tekke, observing these Bird Asmalyks, would have heard and seen everything therein portrayed. I believe these special weavings were strongly phono-pictographic and auto-didactive, when viewed by Tekke natives at the appropriate time. In fact one can distinguish a “near” continuous line surrounding the three lower sides of the Bird Asmalyk, fig. 1, protected by a series of bellowing elephants while the two inwardly slanting superior sides contain designs evocative of a galloping horse’s tracks seen racing alongside arrows being shot at game animals.

The plant forms in the apex region just represent plants. One sees them near the top of the field where the horses are running, the arrows are flying, and the prey animals are fleeing. The plant forms just add a little more realism to the total ensemble of designs in my mind. Following the line between the feathers of almost any arrow form “shot” from ‘the horses’ approaching the apex of the weaving one finds the arrows are properly aimed at the game animals.

A weaving such as this would have been highly instructional and inspirational to every Tekke boy who gazed upon it. It would have resonated with the ambient sights and sounds of that special day to become a spectacular and magical monument to their lives and in their minds. These asmalyks were literally historical records or documents embodying or encoding some of the secret information necessary for mastering the horse mounted archer’s way of life. In this regard they are truly significant historical artifacts and documents of Tekke life and existence. These asmalyks represent to me one of the clearest Tekke self expressions we have detailing their actual way of life.

James Allen